By Claudio Lubis, Analyst, Oil, BloombergNEF

Carbon prices are increasingly touted as a key decarbonization tool for policymakers, but they can have very different impacts on investment, inflation and price volatility depending on how they’re applied.

Take the most commonly referenced scenarios for net-zero emissions and keeping global warming within 1.5C from the International Energy Agency (IEA) and the Network for Greening the Financial System (NGFS). The agencies paint two contrasting worlds, one with sky-high carbon prices, and the other with lower prices that complement targeted policy measures.

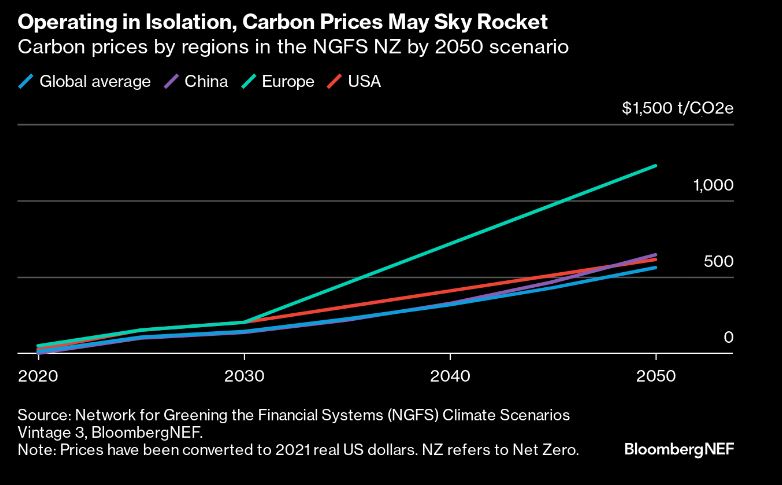

NGFS: Carbon prices as the key decarbonization lever

In both the orderly and disorderly net-zero scenarios from NGFS, an increasing price for CO2 ushers in rapid decarbonization measures and reduces fossil-fuel demand. Carbon prices are defined as the marginal abatement cost of an incremental ton of greenhouse gas emissions, implying that regions and sectors will only decarbonize once carbon prices match abatement costs.

Prices rise to astronomical heights across different regions in the scenarios to reflect varying marginal abatement costs, with the orderly scenario seeing levels for Europe surpass $1,000/tCO2e by 2050, followed by China at over $640/tCO2e.

In the disorderly scenario, the fragmented nature and pace of decarbonization sees various sectors reduce emissions at different rates, with the building and transport industries seeing prices surge to over $950/tCO2e by mid-century.

An extremely elevated carbon price could act as a signal for policymakers to introduce more stringent measures as it would signal that economics alone aren’t working.

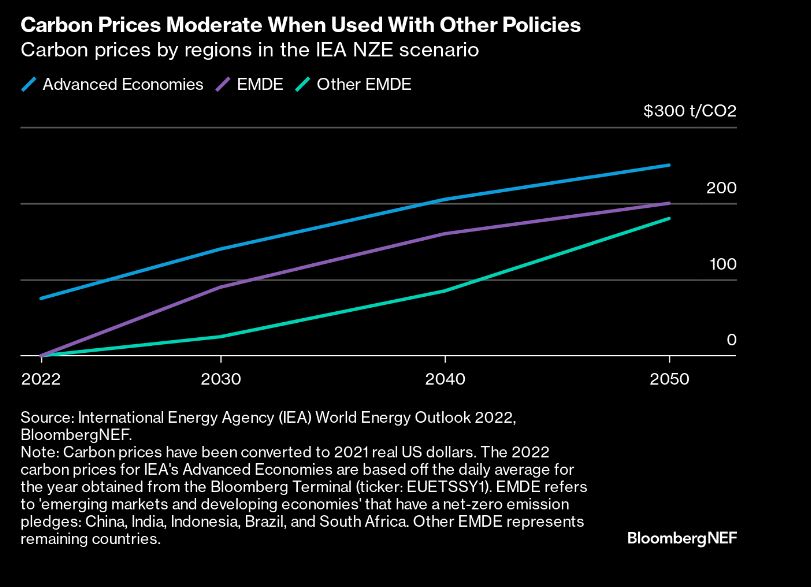

IEA: Carbon prices complement policy

The IEA Net Zero Emissions (NZE) scenario sees a less central role for carbon prices, with policy lifting more of the weight on the way to net zero.

Carbon prices are used as a decarbonization lever in conjunction with the uptake of energy and technology policy mechanisms (and other accompanying measures, such as a ban on new ICE car sales by 2035) and don’t reflect the marginal costs of abatement. As a result, the prices of carbon are significantly lower than that observed in the NGFS scenarios.

By 2050, the price that ‘Advanced Economies’ will have to pay rises to $250/tCO2, while levels are lower for emerging and developing economies at just over $180/tCO2. These latter regions are assumed to pursue more direct policy approaches to decarbonize their energy systems. For context, BNEF expects carbon prices in the EU ETS to be around $170/tCO2 in 2030, slightly above the $140/tCO2 earmarked by the IEA for the same year.

The impact

Despite reaching very similar end-points, the two organizations’ methodologies may lead to sharply differing dynamics in capital investment, inflation and volatility.

For the IEA NZE, a demand-replacement approach will likely see a gradual reduction in traditional fossil-fuel prices, in turn reducing the likelihood of inflationary pressure in carbon-intensive commodities.

In the NGFS scenarios, the central role that carbon prices play may keep fossil-fuel prices elevated, causing energy price inflation to linger for longer.